by Scott Cherry—

|

Recently someone told me, "History is history". I think he meant that history is just the facts, not conjecture. It struck me because there are skeptics of history who think we can know almost nothing about the past. Apparently this person was not one of those. Since it was not the main thread of our discussion I took it at face value. But if this is even a partly true statement, it is as true of Christianity as much as any other subject of history.

|

|

This is an article I wrote originally as a current series of Facebook posts in a group called "The Bridge". That series is called "The History of Christianity". Its focus is exclusively on the formative years of Christianity and its small number of primary founders in the 1st century only. Of course, every history relies on sources, and Christianity is no exception. My source is the historian Luke. First I will introduce Luke, and next I will introduce a modern historian, Sir William Ramsay, to tell us more about Luke and the credibility of his writings.

|

Part 1 Luke the Historian

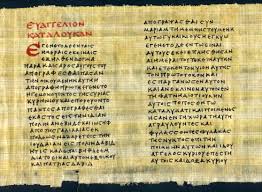

There are two works of history that are widely attributed to Luke: the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts. Both are contained in the New Testament collection, or canon of the Bible and together they are considered by many as one book known as Luke-Acts. This is because in terms of historical literature, the book of Acts bears almost identical characteristics to the book of Luke and picks up the trail where Luke leaves off, as a sequel does. Together, Luke-Acts comprises the lion's share of New Testament material, making Luke the most prominent writer of it (not Paul). It is worthy of note that although his works are regarded as divine revelation by Christians, this was not something claimed by Luke per se (i.e. he was silent on that). Luke's confident claim was that of a credible historian: that his was a historically reliable account of true events and discourses in the formation of the Christian faith-movement. As such his works are replete with impeccable historio-political and geographical details that can be historically examined and either verified or falsified as the case may be. This is indeed the mark of a credible historian.

There is some skepticism about Luke's authorship of these two books, which is hardly uncommon for historians of ancient documents. The evidence for Lucan authorship is inferred from references to a man named Luke in the writings of Paul (Col. 4:14, 2 Tim. 4:11, Phil. 24) whose descriptors fit those of Paul’s travelling companion and the writer of Acts well. Thus he is accepted as the author by many scholars such as Sir William Ramsay who will receive more attention in part 2c. From these references and other clues (e.g. the absence of references to him in the three other New Testament biographies of Jesus) we can confidently infer that Luke was a contemporary of Jesus. He possibly was not present on the scene until after Jesus's departure, but quite possibly was. Either way, he certainly did appear on the scene, probably during the early years of the movement when the eyewitnesses were readily accessible, if not personally known, to him. Thus the writer's accounts in this biography by his name were possibly not his own eyewitness testimony as the reports of the other three biographies were purportedly theirs, but they certainly were based on the first-hand testimony of eyewitnesses which he would have obtained through the historical exercise of interviews, fact-finding/checking, corroboration, and other forms of investigation that are the work of serious historians such as he was. With respect to his sequel, however, (Acts) the situation was plainly different. As already stated, the book of Acts contains references to Luke as a traveling companion to Paul, thus making him an eyewitness reporter of the events and discourses in the second half of the book at least. From that point his account takes on distinctive auto-biographical qualities akin to those of a first-hand travel log.

But even if Luke's authorship of Luke-Acts is uncertain, several things are certain. 1) that someone wrote them; 2) that the writer was an historian of the highest caliber as judged by the impeccable precision of his content; 3) there was a man named Luke whose name appears in the documents who reasonably fits the criteria of the writer of Luke-Acts. In other words, in historiographical terms there are two ways to know about any historian to whom a work is attributed—either a) by external evidence, i.e. outside sources that tell us about the man himself; or b) by internal evidence, i.e. analyzable clues from within the attributed document. In the case of the latter, the 'forensic' precision of the historical information contained in Luke-Acts is first-rate. To substantiate this claim further I will now introduce Sir William Ramsay.

Part 2 Sir William Ramsay on Luke

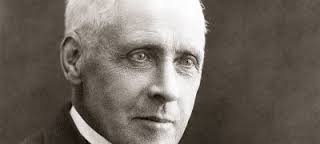

Again, Luke was a first-century historian of the highest caliber who skillfully and accurately documented the nascent years of Christianity and the church starting with the nativity or birth of Jesus (Luke 1-3). In chapter 3 he even included a genealogy rooting Jesus in Jewish history as a descendant of Prophet-King David. I have asserted that Luke's writings are eminently trustworthy to give us an accurate historical account of Christian origins and development in the first century. I didn't mention that in his accounts Luke reached back into Jewish history well before Christ to document ancient messianic prophecies, i.e. those concerning the Messiah who was to come. Now I want to introduce a modern historian to substantiate the credibility of Luke. That historian is Sir William Ramsey, 1851-1939.

There have been several scholars by this name so it is important to identify the one I am speaking of; not Ramsay the chemist but Ramsay the world renowned Scottish archaeologist and historian. He was a specialist in the history and geography of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) where much of Luke's book of Acts occurred. Ramsay was trained in the Tubingen school of thought which was skeptical about the historical accuracy of the New Testament, and he too was skeptical. The Tubingens held that Acts was historically unreliable because they assumed that it was produced in the second century rather than the first century. But when he launched into an in-depth study on first-century Asia Minor there was such a dearth of information from other sources that he turned to Acts in desperation. And he found it to be the best source of all! As a result, he gained enormous respect for Luke the historian and became a strong proponent of the Lucan accounts as found in the New Testament of the Bible.

During his distinguished career first as Professor of Classical Art and Architecture at Oxford and later Regius Professor of Humanities at Aberdeen, Ramsay became world-renowned in scholarly circles and was knighted for his contributions to his fields of research. He was awarded three honorary fellowships from Oxford and honorary doctorates from nine other prestigious universities. He also received honorary memberships to nearly every historical society. This is the man to whose Legacy we look now. Ramsay became an expert on Luke and an unashamed champion of the Lucan accounts of Christianity.

Among historians William Ramsay was of the first rank. But he was ambivalent about Christianity, at best. Some say he was an atheist-turned-Christian, but I cannot substantiate this presently. In any case, he certainly had no special interest in promoting the Bible or the Christian faith (and it doesn’t matter for the present discussion). Indeed, as a skeptic his bias was just the opposite. Like other Tubingen scholars of his day, Ramsay assumed that Lucan and other Christian writings emerged late—well after the events they claimed to report—and were largely the stuff of legend and mythology; not something that could be historically substantiated. But in his research he was surprised by the veracity of Luke’s writings. Despite his early dismissal of the New Testament's (and Christianity's) historicity, he became convinced of the impeccable accuracy of Luke-Acts, and by extension the other biblical gospels, or biographies: Matthew, Mark, and John. Ramsay's research led him to conclude that the early history of Christianity was NOT legendary at all, but one that was entirely rooted in true historical facts.

At first he sought only to verify one particular fact, and it checked out. Logically, that opened the door for more fact-checking. As Ramsay dug into the Luke-Acts narratives his approach was strictly rational and critical, not faith-based. He correctly assumed that documents such as these were subject to the same methods of historical analysis as are all historical documents that are not mere legend or myth, and could be either verified or falsified. His methods were simple and straightforward: to painstakingly comb through the Lucan narratives to identify all details with historical value for verification. That is, any statement of fact with reference to date, geography, politics, and archaeology could be scrutinized, i.e. tested for historical accuracy by historical cross-referencing. That is what Ramsay did because that is what good historians do. There was nothing novel about his approach or methods, except that he applied them to the Lucan accounts in the Bible. Any historian could have done what Ramsay did, but he was the first to do it to Acts, or at least the most systematic. His findings astonished him! He found no historical inaccuracies, or errors, and a great many verified facts. Indeed, in the book of Acts alone he identified 95 geographical details* which proved to be accurate, and still more in other categories. He also found many in Luke. (Later he analyzed the other three gospels using the same methods to corroborate Luke's facts with theirs; and still later, Paul's letters.) They always passed the test.

Ramsay concluded that if Luke had wanted to write a legend (or if he had written his works in the 2nd century) he would not have included so many of these falsifiable details (or could not have). They would only have weakened his accounts if they were not true. Writers of legend or mere fiction would not want to subject themselves to such intense scrutiny as that; it is not in their interests. Rather, they would leave those kinds of details out. But Luke included them. That means he invited scrutiny! He wanted later readers to check his facts. He wanted his accounts to be reputable in every respect. And that means he was telling the truth. If Luke was telling the truth with regard to the 95+ facts (which for a legend would be irrelevant and compromising), then he very reasonably told the truth about everything. No historian goes to such lengths—nor possesses the intellectual prowess—to include this many true facts if he is making up the rest of his story. And that is what Ramsay concluded about Acts. Thus he went from skepticism to confidence in the early Christian history. Thank you, Sir William Ramsay, for your lasting contribution to the historical scholarship of Luke-Acts.

______________________________________________________________________________________

*Appendix: Examples of Historical Details Verified by Ramsay

The following are just a few examples of the 95+ geographical and other kinds of details Ramsay verified. These can be found in Ramsay’s books which are accessible here: http://bit.ly/1t2HZnQ. I obtained these examples from Carm.org (https://carm.org/) whose author lists his references therein.

There are many archaeological digs that corroborate Biblical records on places such as Bethsaida, Bethany, Caesarea Philippi, Capernaum, Cyprus, Galatia, Philippi, Thessalonica, Berea, Athens, Corinth, Ephesus, etc.

The following are historical facts that were corroborated by William Ramsay’s research:

"The historical trustworthiness of Luke has been attested by a number of inscriptions. The ‘politarchs’ of Thessalonica (Acts 17:6, 8) were magistrates and are named in five inscriptions from the city in the 1st century AD. Similarly Publius is correctly designated proµtos (‘first man’) or Governor of Malta (Acts 28:7). Near Lystra inscriptions record the dedication to Zeus of a statue of Hermes by some Lycaonians, and nearby was a stone altar for ‘the Hearer of Prayer’ (Zeus) and Hermes. This explains the local identification of Barnabas and Paul with Zeus (Jupiter) and Hermes (Mercury) respectively (Acts 14:11). Derbe, Paul’s next stopping-place, was identified by Ballance in 1956 with Kaerti Hüyük near Karaman (Luke 2:2) and to Lysanias as tetrarch of Abilene (Luke 3:1) have likewise received inscriptional support." (The New Bible Dictionary, 7, 1957, pp. 147ff.). Luke’s earlier references to Quirinius as governor of Syria before the death of Herod I (Luke 2:2) and to Lysanias as tetrarch of Abilene (Luke 3:1) have likewise received inscriptional support." (The New Bible Dictionary).

At Ephesus parts of the temple of Artemis have been uncovered as is mentioned in Acts 19:28-41. (The New Bible Dictionary). Acts 19:28 says, "And when they heard this and were filled with rage, they began crying out, saying, ‘Great is Artemis of the Ephesians.’"

Luke's account of Lysanias being the tetrarch of Abiline in about A.D. 27 (Luke 3:1). For years scholars used this "factual error" to allege that Luke was wrong because it was common knowledge that Lysanias was not a tetrarch but the ruler of Chalcis about 50 years earlier than what Luke described. But an archaeological inscription was found that said that Lysanias was the tetrarch in Abila near Damascus at the time that Luke said he was. It turns out that there were two people name Lysanias, and Luke had accurately recorded the facts.

An inscribed stone was found that refers to Pontius Pilate, named as 'Prefect of Judaea.’ (The New Bible Dictionary). Luke 3:1 says, "Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea . . . "A decree of Claudius found at Delphi (Greece) describes Gallio as proconsul of Achaia in AD 51, thus giving a correlation with the ministry of Paul in Corinth (Acts 18:12)" (The New Bible Dictionary). Acts 18:12 says, "But while Gallio was proconsul of Achaia, the Jews with one accord rose up against Paul and brought him before the judgment seat."

"It is known that Quirinius was made governor of Syria by Augustus in AD 6. Ramsay discovered several inscriptions that indicated that Quirinius was governor of Syria on two occasions, the first time several years prior to this date . . . [so] archaeology has provided some unexpected and supportive answers. Additionally, while supplying the background to these events, archaeology also assists us in establishing several facts: (1) A taxation-census was a fairly common procedure in the Roman Empire which occurred in Judea, in particular. (2) Persons were required to return to their home city to fulfill the requirements of the process. (3) These procedures were apparently employed during the reign of Augustus (37 BC–AD 14), placing it well within the general time frame of Jesus’ birth."

"No archaeological discovery has ever contradicted the Bible. Therefore, since it has been verified over and over throughout the centuries, we can continue to trust it as an accurate historical document." -Matt Slick

*Here is another excellent website that contains much of the same information and even more examples: Stand to Reason: The NT is Archaeologically Verifiable.

*Here is another one with attention on Luke-Acts: http://www.ichthus.info/Luke/intro.html

*Here is one that gives attention to all four gospels: https://bit.ly/36lZPpY