|

John Wycliffe was born in England, 1331. He was a philosopher and theologian that wanted to see the Bible translated into English. He is sometimes referred to as the Morningstar of the Reformation, but his English translation occurred before the printing press and his work was done without leaving as much of a footprint compared to later reformers. His work was based on the Latin Vulgate which was translated from the Greek by St. Jerome in the 4th century. It was a translation of a translation. At the time, and throughout the middle ages, people did not typically read the Bible for themselves. Priests read the Bible and conveyed the meaning usually using the Latin translation. People were illiterate and the images and statues were an important part of the faith as it helped people grasp the stories of the Bible. Wycliffe’s idea to make the Bible accessible in the language of all people is not a new one. The early Christians translated the New Testament the moment it was created. They all wanted to know it in their own language. We have Coptic manuscripts from the 1st century. Syriac translations from the 5th century and Latin from the 2nd century. These were all translated from the original Greek.

About 100 years after Wycliffe, Desiderius Erasmus published the Greek New Testament. His was the first since the originals were written. Of it he said “the Greek New Testament is the New Testament. All else is translation”. A contemporary of Erasmus named William Tyndale was an English scholar who wanted to carry on the work of Wycliffe and make the Bible understandable to every English “ploughboy”. However, he did not work off of the Latin text, he translated the Greek text of Erasmus and the Hebrew Old Testament, and it was the first English Bible to do so. He was threatened by the church and was forced to flee from England. His first English edition was published from Germany in 1526.

After political upheaval in England, it seemed to have become necessary to create an authorized version which later became known as the King James Bible. There is no evidence that the Bible was actually authorized by the government in spite of the name. The work was performed by teams of theologians and it also was translated from the Textus Receptus (TR) (Erasmus’ Greek Bible meaning received text) and the Hebrew Old Testament. This was the best of scholarship available in 1611. Amazingly enough, about 90% of the King James Bible is taken from the Tyndale Bible confirming the quality of the previous work of Tyndale (and company).

TR was the best Greek text available. How do we know that the Greek text of Erasmus is the authoritative text? What if it was changed over 1500 years? In walks a discipline called textual criticism. Textual criticism is not a theological discipline about what the text might mean, it is only interesting in retrieving the author’s original words. Manuscripts are dated by the type of material used, the style of the writing, references to historical events, and several other factors. If a later text disagrees with a number of earlier texts then we can know a change occurred.

“The task of textual criticism is to exhibit what the original writer intended to communicate to his readers, and the method is simply that of tracing the history of the document in question back to its beginning, of, and in so far as, we have the means to do so at our command” Eberhard Nestle (1851-1913)

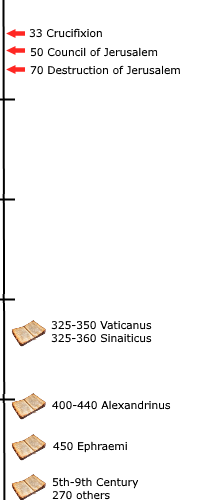

By 1862, some amazing discoveries were made. In the 4th century, animal skins were used as parchment and this practice was much more durable than the papyri that was used in the time of the NT. Two complete (or mostly complete) Bibles were located. One in St Catherine’s monastery in Egypt called Codex Sinaiticus (a codex is a book versus a scroll). Because of notes in the margins, the codex was undeniably dated between 325 and 360. The other is codex Vaticanus also dated to the 4th century.

Beyond these 2 earliest codices, we have about 270 others dating from the 5th to the 12th century. So, what do these earliest codices tell us about the Bible we have today? They tell us that it has been incredibly preserved. Using the earliest, we can tell if some passages were added, changed, or removed over time.

Interestingly enough, we have found that, in the few case where changes are detected, verses are usually added, not removed. Experts feel that this is because a theological thought or even a piece of oral history would coincide with a particular passage and the Scribe or Monk would add the thought in the margin of his piece of Papyri or parchment. Our Bibles are from a printing press and you can differentiate the text from the margin notes you write yourself but here you could not always differentiate. The thought would be copied and the notes would find their way into the text over time. One might think this would happen quite often but it did not for a myriad of reasons that we will cover next time.

There are 2 major passages that are sometimes presented as only examples, when in fact they represent a large portion of the variants (a change) that we can detect. They are John 7:53-8:11 and Mark 16:9-20. Any modern Bible (NASB, ESV, NIV) will have a footnote on these passages letting you know that they are not in the earliest and most reliable manuscripts. No variant represents a theological change. No Christian doctrine is based on these variants. This is a very important point.

For example, the KJV has an inserted statement at 1 John 5:7. 1 John 5:8 says “And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.” One scenario might be that a scribe very early on had a very interesting thought, that there are also 3 that bear record in heaven and possibly made a little note for himself of a strong Trinitarian statement. Maybe he made the note in the only space he had left on his piece of parchment. Someone liked the statement or thought it was part of the text and confirmed a theological doctrine that they held to, so it was added to the text as 1 John 5:7 “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. 1 John 5:7 KJV.

This insertion is not the reason that Christians are Trinitarian. It is actually a proof that the Christians at the time of the insertion were Trinitarian. No doctrinal change was made and the Trinitarian formula was never based on this text. We can prove that by pointing out that this verse was not present in the earlier texts.

The book of Mark (without the long ending) ends very abruptly with the two women running out from the tomb and saying nothing, because they were afraid. Mark, possibly writing with the persecuted Christians of Rome in mind may have wanted to make a dramatic appeal. The two women were afraid and did not tell anyone. Are you afraid? Who will you tell about Jesus? Of course, after the persecutions ended and the book is disseminated then it is possible that the long ending was first in someone’s footnotes and made their way into the text. It is also possible that Mark himself added the long ending. The long ending is quoted by Justin Martyr and Irenaeus very early on in history. Some biblical critics like to assume theological motives to additions but then why exclude the original motives of the author. Of course, this is speculative and it is likely to have been added by later scribes from the other gospels. In fact, the long ending of Mark appears to be a pastiche from the other 3 gospels and Acts.

|

Verse

|

Content

|

References

|

|

Mark 16:9

|

Jesus rises on the first day

|

Matt 28:1;Luke 24:1, John 20:1

|

|

16:9

|

Appears to Mary Magdalene

|

John 20:11-18;Matt 28:9-10

|

|

10

|

Women’s report to others

|

Luke 24:10; John 20:18

|

|

11

|

Unbelief at the report

|

Luke 24:11

|

|

12

|

Jesus appears to 2

|

Luke 24:13-32

|

|

13

|

Report to the others

|

Luke 24:33-35

|

|

14

|

Jesus appears to the 11

|

Luke 24:36; John 20:19,26

|

|

15

|

Great commission

|

Matt 28:19

|

|

16

|

Belief, baptism, condemnation

|

Matt 28:19;John 3:18

|

|

17

|

In Jesus’s name

|

Matt 28:19

|

|

17

|

Casting out demons and speaking in tongues

|

Luke 10:17-18; Acts 2:4

|

|

18

|

Handling snakes

|

Acts 28:3-5

|

|

19

|

Jesus ascension

|

Luke 24:51; Acts 1:2,9

|

|

20

|

Disciples sent out

|

Luke 9:1-2; 10:1,7

|

|

|

· How we got our New Testament: Text, Transmission, Translation, Stanley E Porter

|

|

|

|

You might ask “Why would God allow this to be added?” The answer is that he didn’t, we caught the scribe and preserved the original text in a way that we can historically verify.

So, we can see the canon (the recognition of the specific books) of the Bible was already complete by 325-360 AD.

We can also see that the text remains overwhelmingly intact. The King James Bible was not perfect but it was very good. With the work of textual critics and dsicoveries since 1661, we can be confident that the English Bible we today is the same as the canon of the 4th century.

As we can see from the image, there is still a long time between the authorship of the New Testament and the full copies that we have now; about 200 years.

How early was the canon of the Bible recognized? Can we get even further back and closer to the original author’s text? Yes, much closer and much further back.

These parchment codices are only one type of historical witness we have. Next, we will see how much closer we can get through the testimony of early papyri – the paper of the first century made by splicing papyrus reeds and pressing them together.

|