"A day without death." (continued from March 7)

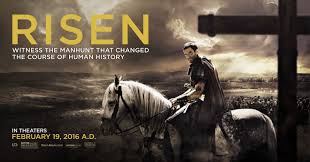

In 1st-century Roman Palestine it had been almost two weeks since the tomb of the executed Jesus was found empty. The New Testament narratives and other historical accounts tell us there were reports of some who claimed to have seen him alive and believed he had risen from the dead. True or not, in some sense Jesus was still causing trouble for Pontius Pilate and the Jewish authorities. They unmistakably killed him and needed him to stay dead to squash the uproar he had created. In the 2016 film Risen a Roman centurion named Clavius was forced to become a detective to find the missing corpse and was reeling from the shock of his discovery that this crucified Jesus of Nazareth may not be actually dead at all. In part 1 of this piece (2 down) I tried to give you a good grasp of the plotline of Risen and some broad brushstrokes about its themes. Now I want to go deeper. Recall the last sentence of part 1 in which I said “…what started as his problem became his salvation.” Let’s explore this further.

|

One of my favorite scenes in the film was within the first 20 minutes, only moments after the scene of the crucifixion. Clavius, the Roman tribune assigned to the service of the governor, Pontius Pilate, was charged with the odious responsibility of hastening the conclusion of the execution before dusk when the Jewish Passover would begin. Immediately before this he had just achieved a victory in a small but bloody battle with Jewish rebels in which one of his friends was killed, and he had not even had time to wash before being beckoned by Pilate and ordered to the crucifixion site. As Clavius the tribune, actor Joseph Fiennes did an excellent job of showing his loathing for his responsibilities. Following the execution he returns to HQ where he was apparently invited to have a hot Roman bath with the governor. Normally this would have been quite a privilege for Clavius but one could not tell by the look of exhausted disdain on his face. Clearly he had earned the respect of his superior for having successfully accomplished two bloody tasks in one day, both of which were dangerous to Pilate’s grip on public order. Yes, order was to be maintained at all costs. Clavius would have been content just to soak away his fatigue in silence but Pilate was in the mood to talk. Their conversation went something like this:

Clavius: “Prefect, I don’t envy your mantle.”

Pilate: “Don’t give me that, it’s your path too. …Your ambition is noted, Clavius. Where do you want it to lead you?

Clavius: “…Rome.”

Pilate: “To what end…?”

Clavius: “Position, power, wealth, a good family …A place in the country.”

Pilate: “Where you will find…?

Clavius: “An end to travail…a day without death…peace.”

Pilate: “All that for peace? Is there no other way?”

This conversation was intriguing to me. It underscores what I think is one of the core drives of every person: peace. Clavius could have said happiness or contentment and it would have captured the same idea. In the end what a person really wants in life is one of these inter-related, intangible things. It reminds me of a song by the rock-and-roll band Boston who released a song in 1976 called “Peace of mind”. The refrain was, “All I want is to have my peace of mind.” Like Clavius, people pursue all kinds of things in life but what they really want, and what they hope all these other things will lead to is peace, happiness, or contentment. They’re the end goal. Sure, pleasure is up there too, but even that is a means to an end. We all want “an end to travail”…and “peace” in its various forms.

Ah, but maybe you noticed that I left something out in the last sentence. Yes, I left out what Clavius said in the middle: “A day without death”. It’s this phrase that I want to focus on for a few paragraphs.

|

On the one hand, this might not seem a very surprising thing for Clavius to say. His job as a Roman Tribune was one that frequently confronted him with death, often at his own hands as when he thrust a sword through the skull of a captured Barabbas*, and often narrowly escaping it himself. The first 20 minutes of the film quite tangibly portrayed this side of his job description, in the course of a single day no less, a Friday. (In the film we know that because it was to be the first evening of the Jewish Passover, which we know in turn because of the entrance of Joseph of Arimathea at the scene of the crucifixion who was in a hurry to obtain the body of Jesus and inter it before sundown.) Of course, many films expose us to death these days, if not also glamorize it. But unlike some characters in other films who revel in killing and death, Clavius does not; he is weary of it. He longs for a time without death, or at least without so much of it. That’s the obvious sense we get from his statement to Pilate in the bath… “a day without death”. Many people can identify with this sentiment. As much as a “normal” part of life as death is, even natural death, it is something that most people only tolerate at best, because they must.

Permit me here to include an excerpt from a previous post about death:

Death qualifies as both a law of nature and a law of logic, as perhaps all laws of nature do. (Paul the Apostle, another biblical philosopher in his own right, calls this “the law of sin and death” in his epistle to the Romans, chapter 8:1.) I will call it an “existential law” to capture both categories, natural and logical. Another law of logic, by the way, the law of identity, states that death = death. Death is not life; they are two different things. On earth, in the temporal realm, all living things die. Everyone, with the exception of some skeptics, would say they know this. Nobody I’ve ever met argues against this fact, and philosophers do not seem to challenge it. They say death is a true fact and even a law. On one level, the physiological one, we know why people die, in general or specific. On another level, the metaphysical one, we do not know (unless one draws from religion/revelation). In other words, we do not know why people must die, i.e. why death is part of reality, only that it is. As with other such laws, all of existential reality is organized in-part around this law. Therefore, people live with the reality of death in mind. For one, we know death is inevitable, but that some things cause it. And most people do not want to die, especially not too early. We know there are many things that can cause premature death. Since people have a drive to live rather than die (another existential law) they do things to protect, sustain and extend life, and to avoid death.

It is plain that our focus here is on the tragedy of death, for Clavius has been over-exposed to it. He is depicted in the film as a man who longs for a day when his lot will change…for “a day without death”. But, one wonders, does he long merely to be insulated from over-exposure to death or is it a deeper heart-cry against the very reality of death? I suspect it is both. The former feeds into the latter.

Fast-forward to a scene in the middle of the movie. Recall from part 1 that during the final hours of his search for the missing body of Jesus, Clavius finally prevails, but not in the way he had hoped. Based on tips from his informants, Clavius locates the whereabouts of the disciples-in-hiding whom, he reasonably predicted, would lead him to the secret of the missing Jesus. After days of arduous investigation, how he must have tasted this! Pausing at the threshold of their lair, he slowly pushed open the door with his sword. The disciples were there, and so was Jesus himself, whom he was not expecting to find there! But rather than a putrid corpse, Jesus was sitting among them—alive and whole! Having had his visage burned in to his memory from the scene of the crucifixion, Clavius almost immediately recognized him as the one whom he had been seeking. But alive! Not surprisingly, this discovery arrested his attention and jolted his understanding of both death and of Jesus. The viewer could easily perceive his shock and his imagine his thoughts by his facial expression: “Am I really seeing this?! Death is permanent, and men who are killed do not reappear alive! This should be impossible, but I see him with my own eyes!” Just then Thomas, one of his disciples, entered and was invited to examine Jesus’s wounds to satisfy his own sense of incredulity. And then Jesus disappeared until a later time. Except for the presence of Clavius, this scene is recorded in the gospel of John 20:26-29, with similar accounts in the other gospels.

Following this unnerving discovery, Clavius could no longer operate as the man he had been before, with his former assumptions about death and the supernatural. His initial investigation was over, but now he must embark on another one, an investigation of his own soul and his previous worldview. To do so, he abandoned his post as tribune and followed the disciples to Galilee where they expected to meet Jesus again. Now fast-forward to a scene in the last 15 minutes of the film. Only a few days later at the Sea of Galilee they joyously re-encountered him while they were fishing together (John 21). That same night while the disciples were sleeping under the stars, Clavius had a private audience with the risen Jesus. This scene is entirely fictitious but, I think, is quite consistent with the biblical narratives. That is to say, allowing for the creative license of the film, this conversation is very much like one I can imagine. Their conversation went something like this:

Jesus: “Clavius, what do you fear?”

Clavius: “Being wrong.” [Interesting discussion can be pondered on this point.]

...Other words were exchanged between them we will omit for the moment.

Jesus: “Clavius, what do you seek?” (with a penetrating stare) … a day without death?

To this Clavius could only look at Jesus in knowing astonishment, and slunk down next to him in the self-restrained tears of a Roman tribune. Jesus was not there when Clavius said these words to his superior the governor. In fact, Jesus was dead and buried earlier that day. This statement by Clavius could only have been known by a man who demonstrated that he had power over death; and in keeping with that power, specific knowledge of what could only be known by one who possessed it. Jesus was reading not only his thoughts but also heart. He knew what Clavius yearned for, yes, a day without death.

Risen does an excellent job of capturing his yearning throughout the film and bringing him to the point of humble realization. Death is a universal dark reality that most people fear and avoid at all costs. Nobody has power of death, not even the most revered prophets. But by his resurrection, Jesus proved something astonishing to the world: not that he could escape death, though that is not hard to imagine given how often he had eluded capture before this. Rather, he proved that he was willing to submit to death for a higher purpose—to commiserate with humanity, yes, and then to defeat it. By defeating death Jesus showed Clavius, all the disciples, and the world that there can and will be “a day without death for those who believe. This is the declaration of the New Testament when it says…

"We know that he who raised the Lord Jesus will raise us also with Jesus and bring us with you into his presence. For it is all for your sake, so that as grace extends to more and more people it may increase thanksgiving, to the glory of God. So we do not lose heart. Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison…" (2 Corinthians 4:14-17)

and…

"If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you." (Romans 8:11)

And in Jesus’s own words…

“I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die.” (John 11:25-26)

In still another place Jesus put forth his mission statement very succinctly: “I have come that they might have life and have it abundantly”. So there you have it. Jesus was not about death. Nor was he about killing and conquest and subjugation, as some other religious leaders have been in history, and a great many others.. He did not lead armies nor teach his followers to engage in warfare in order to spread Christianity. He came to bring life…eternal life, and the peace that accompanies the assurance of it. In fact, Jesus came to destroy death.

Jesus came to offer a day without death. And, because of his resurrection from the dead he proved that he was eminently qualified to give it to all who would trust and follow him.

Postscript

*Barabbas is a rebel figure who was named only once and appears at the end of the opening battle scene. He meets his demise quite dramatically at the hand of Clavius for having participated in the Jewish insurrection that Clavius was responsible to put down. The film suggests that Barabbas even led it, but the story tells us nothing else about him. The viewer would only know the backstory from all four gospel accounts in which we are told that he was already in Roman custody for previous crimes at the time of Jesus’s trial. These accounts tell us he was released instead of Jesus by the unbridled demand of the mob in the court of Pilate the Roman governor. Matthew includes the most details as follows:

Now at the feast the governor was accustomed to release for the crowd any one prisoner whom they wanted. And they had then a notorious prisoner called Barabbas. So when they had gathered, Pilate said to them, “Whom do you want me to release for you: Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?” For he knew that it was out of envy that they had delivered him up. …Now the chief priests and the elders persuaded the crowd to ask for Barabbas and destroy Jesus. The governor again said to them, “Which of the two do you want me to release for you?” And they said, “Barabbas.” (27:15-21)

After this point the gospel narratives are silent about Barabbas and the creative license of the film makers kicks in. They apparently assume that the informed viewer can easily surmise that upon his release Barabbas immediately started the rebellion which resulted in his on-the-spot execution. (This seemed entirely reasonable to me.) The gospels’ information about Barabbas exemplifies the kind of detail that lends credibility to the passion accounts as a whole, i.e. the arrest, the trial, the intermediate scourging and the condemnation that led to Jesus’s final execution. Other than the gospel writers’ concern for accurate reports there would be no reason to include any information about Barabbas.

Click here for part 1 (March 7): CSI Palestine, part 1